Film Review: The Big Parade (1925)

The Big Parade (1925)

directed by King Vidor

Frames in this review are taken from the 2013 Blu-Ray release.

Originally written May 2005 from a viewing of the 1988 VHS release.

There two halves of The Big Parade are so different in tone that they're almost two films. If we were to give them titles, the first half could be called Life in the Army, a nostalgic look at the camaraderie of basic training and garrison duty. The second half could then be called War is Hell, a nightmarish experience of the trench warfare that dominated the First World War on the Western Front. This intentional stylistic dichotomy gives the film the same perspective as the American doughboys had in the Great War. A rapid transition from peace to war, a burst of patriotism, a baptism of fire in intense combat, and then victory just 19 months later.

In contrast, the principal European combatants attempted to fight a 19th

century war of maneuver in 1914, before deadlocking in the trenches for

the next three years. An entire generation of young men was cut down by

the millions. Food shortages ravaged civilians in blockaded Germany and

Austria-Hungary, élan gave way to mutiny in the French Army, and revolution

swept Russia into an uncertain future. The exhaustion of the First World War

is better captured in that other great anti-war film

All Quiet on the Western Front, which takes the viewer through all four years of

the war, sends the protagonist into attacks and counterattacks and advances

and retreats, spends a painful stretch in a field hospital, and follows

him home on leave to a world that does not understand his anguish.

While All Quiet on the Western Front achieved its impact by soaking up the desperation as it accumulated over four long years, The Big Parade shocks the viewer with its rapid change of tone that quickly drives out any naïveté about war. We are first treated to an hour of horsing around and chasing French girls, lulling us into a false sense of security. Then WHAM! The paradisiacal world comes crashing down, and the protagonist is thrown into the relentless whirlwind of combat.

That so much bitterness can develop from a (comparatively) brief exposure

to combat makes a rather different and even more forceful statement on

the horrors of war. Half a century later, Peter Weir's Gallipoli (1981)

would take this approach even further — the characters do not get thrown

into combat until the very end of the film. Then, they are cut down by machine

gun fire as they make their one valiant attack for God, King, and Empire.

Denouement comes outside the cinema as the stunned audience staggers back

home.

Summary

To create this false sense of well-being, The Big Parade takes care to keep the war far away at the outset. The young protagonist James Apperson (John Gilbert), enlists in the army out of the shallowest sense of patriotism. He’s swept along by the flags and the parades, by the peer pressure to join up, certainly no sentiments of "Let's make the world safe for Democracy." Basic training is swiftly dealt with in a quick montage of marching, and the civilian-clad volunteers dissolve into a neatly uniformed body of troops in less than a hundred feet of film.

In France, the soldierly life is shown to be bucolic and fun — washing clothes along a stream, raising hell in town, running from MPs, receiving letters and cakes in the mail, juggling the French girl Melisande (Renée Adorée) with the Girl Back Home. "This ain't such a bad war," says army pal Bull (Tom O'Brien) in an intertitle. If it were not for their army uniforms, the characters might as well be a group of students visiting on holiday. The only link to the war is a scene in Melisande's home as her extended family reads letters from the front, but this scene is played comically, with the grandfather striking poses and stabbing a sword, as though he were marching "On to Berlin!" in the confident army of Napoleon III.

The romance between Jim and Melisande is told in a series of too-cute episodes. Of course it has to start with Jim making a fool of himself, as he first encounters Melisande while carrying a barrel — from the inside. Jim then introduces Melisande to the American institution of bubble gum — which she promptly swallows. Later Jim sees a frog and points it out: "He ... froggie! You ... froggie!" But a letter from the Girl Back Home dampens their relationship. Nevertheless, Jim decides to stick with the French girl, leading to a joyous reunion.

But the reunion is fleeting, for it comes just as the unit is ordered to the front line. A brief telegraphed order is shown, almost exactly at the midpoint of the film, bringing a blast of bugles and a flurry of activity. Thousands of men, horses, carts, and trucks kick up a storm of dust on the streets, as Melisande frantically searches for her man amidst the commotion. MGM gets to show off the vast scope of the production as we see what looks to be the entire 2nd Division of the U.S. Army roll by. The intertitles play up the urgency with repetitive phrasing in all-caps and exclamation points. The trucks roll away, and Melisande is left alone in the street. The intermission originally came at this point, neatly separating the two stylistically-different halves of the film.

After intermission comes the titular Big Parade, a seemingly endless line of trucks carrying men to the front along a narrow road. The massive column is majestic, exciting, and stirring, but it’s also the last such scene in the film. There will be plenty of excitement later on, but it will not be the happy kind. There is no glory to be found in this war. As the soldiers march to the front on foot, the column is welcomed by a German fighter plane that dives down and strafes them. As they approach trees intended to represent Belleau Wood, they pass a line of ragged French wounded heading the other way. They get their first taste of battle as they advance slowly through the woods in skirmish lines, as snipers pick them off one-by-one and machine guns knock them down by the dozen.

No sooner are they through the woods than they are welcomed by an artillery barrage from the German guns. "They're not going to send us out in that open field, are they?" asks Jim. "Sure! We're gonna keep goin' till we can't go no farther!" replies his friend Slim (Karl Dane). The American Expeditionary Force has got fresh men to spare, and they'll take as many casualties as they need to drive the Germans out.

Later, there's an agonizing night patrol that is harshly illuminated by flares. Brave soldiers scream in agony while their comrades listen helplessly from trenches mere yards away. A wounded Jim ends up in a shell crater with a wounded German soldier, whom he hesitates to kill and finally offers a cigarette. Then the main attack begins with an all-out night assault that is lighted by explosions and gunfire. Villages are taken and retaken, civilians turn into refugees, and hospitals are filled with the shattered bodies of the barely alive. Even the homecoming is bitter, although a Hollywood film ultimately has to have a happy ending. Jim returns to France and is reunited with Melisande.

Mood

The Big Parade is fairly sparse in its use of intertitles. You almost get the feeling that some of them were inserted because they'd gone too long without one, as in the entirely self-explanatory frog scene. But the non-conversational intertitles help to set the mood for the images. For example, the reflections on patriotism ultimately motivate Jim's enlistment during the parade, and the excited large-type repetition adds urgency to the division’s departure for the front. This combination of text with imagery was a form of artistic expression that was available to silent films in a way that would appear stilted in a sound film.

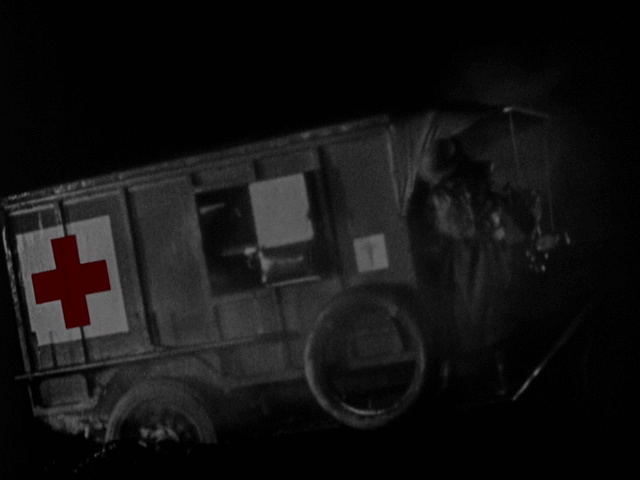

The two most memorable intertitles are brief yet eloquent. First, there is the all-caps "BIG PARADE" that accompanies the proud army heading to the front. After the battle, there is a shot of a wheel stuck in the mud, a pullback to show the red cross on the ambulance’s side, and then a seemingly endless line of ambulances on the same road, this time heading away from the front. This scene is introduced by the title "Another Big Parade." The ironic repetition of the title bookends the combat scenes in the film. The sparing use of words creates a forlorn feeling that is difficult to create with images alone.

The acting is superb, restrained and confident in an example of silent film at its height. John Gilbert can stare into the camera with insouciance, as when he's chewing gum with Melisande. But he can also stare with alienation, as when he is stuck in hospital and tells a babbling man with shell shock to shut up, or when he's sitting wordless in the car with his father on his way home.

The character actors playing his pals open up in free-ranging performances. The bartender Bull becomes a corporate and is the constant butt of the privates' pranks, while Slim the riveter is the simpleminded and happy-go-lucky type. This sets up an interesting contrast when they go into battle for the first time. Jim is tense and frightened, while Slim is delighted at the change of pace, nonchalantly shooting a sniper and blissfully unconcerned about advancing into an artillery barrage. Renée Adorée presents a charming Melisande, at first reluctant, then agreeable, then angry, then feverishly desperate, and finally longing. You don’t need synchronized sound to convey deep human emotions.

The camera work in the film is fairly unobtrusive. There are lots of tracking shots — dollying across soldier's faces, keeping up with moving vehicles, staying in front of the advancing soldiers in the forest — but no dramatic camera tricks. Many of the romance scenes are shot in static setups. But the night battle scenes are spectacular, with the staccato lighting of the flares adding tension to the sleepless night. Here, the constrained camera viewpoints fit in well with the trench occupants’ lack of mobility.

The double-exposures of the big night attack create a dynamic and astonishing scene as the unrestrained explosions are overlaid onto the relentlessly advancing men. There's debris flying everywhere, smoke all around, and constantly changing lighting. The double-exposure also has the effect of reducing the contrast in the scene, making the soldiers’ figures look like ghosts, as though they were men already dead but still marching onward. Yet again, art flourishes within limitations. The danger of sending stuntmen into a field littered with explosions forced the double exposure, which created an artistic effect.

The montage of Jim's mother thinking back over his childhood as they

embrace at the homecoming is now the oldest cliché in the book. But audiences

were not yet jaded in 1925, and in a film with no spoken dialog, the images remain

potent and the flashback holds on screen for just the right amount of time.

Hugh Wynn, who would later also edit Vidor's

The Crowd [link to review] and

La Boheme

, also cut The Big Parade. Of course,

Vidor himself was also very concerned with timing. Famously, he used a

metronome when filming the advance through Belleau Wood, creating a

sense of tension through a slow and deliberate pace, as though it were

a funeral march.

Another interesting point about this film is the diegetic music. Diegetic music in a silent film? Sure, in the intertitles. The lyrics of songs like "You're in the Army Now" punctuate scenes of army life, often as the soldiers are actually singing. Carl Davis has picked up on these cues in his modern score. Much of the music comes from recognizable songs: "Over There" in the American cities as the armies are raised, "La Marseillaise" in Melisande's house as the grandfather fights off the imaginary Prussians, and of course, "Mademoiselle from Armentières." Carl Davis' score is at its best in the frantic assembly scene that comes just before the intermission, in which the military theme fights the love theme for supremacy. Cymbals crash as Melisande searches desperately for her love, trapped in the middle of the road between a column of marching infantry and a column of horse-drawn artillery. It's almost like opera without the singing.

Technical

The original negative for the film had long been thought to be lost. When British film historian Kevin Brownlow collaborated with composer Carl Davis in the 1980s to breathe new life into Hollywood silent classics in the Thames Silents series, the best surviving element was the MovieTone synchronized sound version from 1931. MovieTone cropped out the left 1/6 of every frame to make room for the optical soundtrack, resulting in an aspect ratio of 1.16 to 1. A full-frame 1.33 silent film showed unbalanced compositions. Shots of Jim and his two army buddies would invariably show only 2½ soldiers. The film was also heavily scratched and lacked all the color tinting, resulting in such incongruities as a plane flying across a bright day sky in what was supposed to have been a night scene.

In 2002, Kevin Brownlow was revisiting the film at George Eastman House when he discovered that the original negative still existed after all. [Link to March 13, 2005 Los Angeles Times article] The reels had simply been mislabeled. The full-frame silent version had been mislabeled as the cropped MovieTone version. The film was then restored from the original negative, with the color tints being recreated from the continuity records, and the single hand-colored scene digitally recreated. [Link to article on the restoration by Warner Brothers Vice President Richard P. May] The restoration was completed in 2005 and made available for projection, but the market for the film was judged to be too small for a home video release. As late as August 2010, Turner Classic Movies was still showing the video transfer from 1988. [Nitrateville discussion on The Big Parade] The restored full-frame original version of the film finally made it to home video in 2013.

The film now looks great. Contrast is excellent for the most part, and dirt and scratches have been scrubbed out digitally in a way that was never possible in the photochemical world. You can pick out many details that were hard to see in the VHS version. For example, background action is now clear as day. As the American soldiers assemble to go to the front, standing on the street by the hospital are nurses, a priest, and several wounded French soldiers: a guy with his head all bandaged up, and a guy with an evident visual impairment wearing sunglasses. This note of discord is notable amid the commotion, especially considering that Jim's reaction to hearing the order was to rub his neck.

The Carl Davis score seems to have been recorded in 2005 — it credits José-Luis Garcia (d. 2011) as the leader of the English Chamber Orchestra. The presentation is credited to producers David Gill (d. 1997) and Kevin Brownlow, and the last title card still credits Thames Television. The film is presented at 20 frames per second, which is a little slow for a late silent. The Belleau Wood sequence is supposed to be slow, and the assembly sequence is such a flurry of activity that it benefits from being run at 20 fps. However, some of the non-action scenes, especially in the first half of the film, really drag at 20 fps. The intermission is not noted.